CIAMS Ph.D. students Rebecca Gerdes and Annapaola Passerini were awarded NSF DDRI grants.

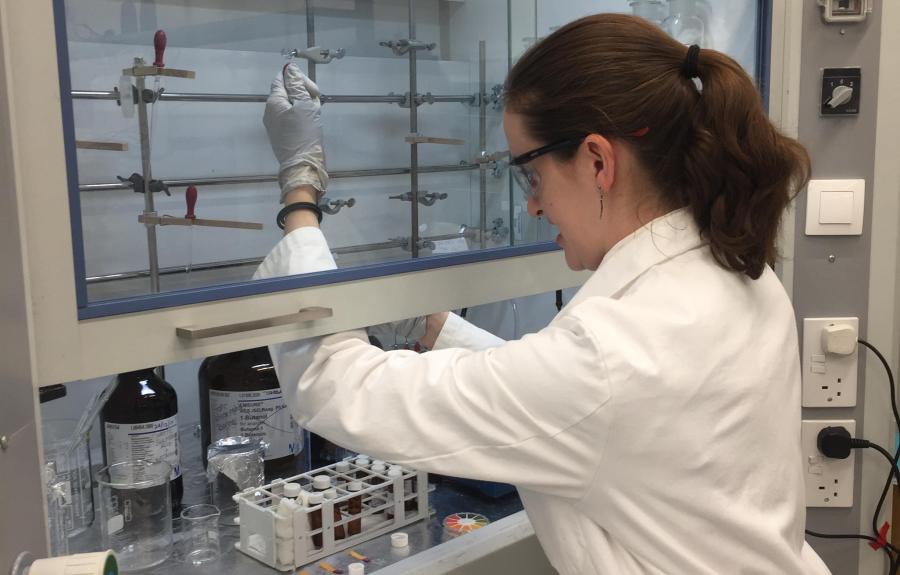

Rebecca Gerdes is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Classics. Her project is titled, "Developing a more robust approach to organic residue analysis for the study of ancient Mediterranean foodways.”

From the abstract:

Food is foundational to everything from daily life and the economy to social connections and religious practices. Archaeological finds of ancient pottery offer an abundant source of material evidence for the ways people stored, prepared, cooked, and ate food from prehistory to today. Traces of food preserved in the pores of pottery provide direct evidence for how people used their pots in the past; combined with radiocarbon dating of individual molecules from these food residues, they are a powerful tool for reconstructing the practices that shaped the food systems which form the foundation of today?s global food system. Past scholarship has paid little attention to how the diversity of environments and food sources worldwide might complicate interpretations of what a pot once held. This project will develop a robust approach to interpreting the sources of food residues in pottery that is sensitive to differences in the environment. Through collaborations with researchers in food science, engineering, chemistry, and soil sciences, this research offers contributions to fields such as food science, sustainability, and renewable energy, and unique training opportunities for student research assistants.

The research team will study the complications caused by regional differences in climate and the environment: different conditions can create more than one possible interpretation of the food sources that could have caused the particular collection of molecules observed by an archaeologist in a pot fragment. This problem arises because many foods are made up of similar molecules, or can look similar because of environmental processes at archaeological sites that break down food over time. The researchers will develop methods to combat this problem, focusing on the Mediterranean, a region with a distinctive climate and a uniquely rich archaeological and historical record where key regional food systems developed. By developing a novel laboratory-based experiment that can incorporate different soils in a simulation of the breakdown of different food products over time, the researchers will provide an efficient, region-specific experimental design applicable worldwide, not only for archaeology but for any field (such as food science or sustainability) that requires the study of how food breaks down in soils. Drawing on supercritical fluid extraction, a technique used in renewable energies research, the team will also produce an optimized method for recovering food residues that minimizes the loss of interpretative information about a pot?s contents. The researchers will also evaluate whether environmental differences pose a challenge to using radiocarbon dating of individual food molecules to link the archaeology of everyday life to a historical timeline. By applying these developments to three case-studies the researchers will produce robust datasets that advance the understanding of past food practices and their entanglement in politics, religion, and the economy.

Annapaola Passerini is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Anthropology. Her project is titled, “Absolute Time, Lived Temporality: Generative Chronologies in the Early Bronze Age South Caucasus.”

From the abstract:

Absolute time, or chronology, is fundamental to interpret the past. However, the disregard for how past societies actually experienced time results in a discrepancy between generalized models of socio-cultural change and the diverse experience of life?s rhythms, thus perpetuating the creation of dehumanized histories. How people organize around life?s rhythms, whether as members of a generation or as a society responding to broader environmental or socio-cultural challenges, profoundly impacts the decisions made in the present, thus shaping the course of actions in the long-term. Archaeology is well positioned to solve this tension between absolute and lived time by offering a long-term perspective on the unfolding of human experience. This project will undertake research that uses radiocarbon dating to investigate people?s lived experience of time in past communities.The project also speaks to a wider anthropological conversation regarding the understanding of time as a social construct and the artificial separation between society and ?clock time?. The research includes broad scientific collaboration and encourages training in archaeological science among students and scholars.

The project will investigate how to identify different dimensions of lived time from material remains, which will offer a new approach for archaeologists studying socio-cultural changes in the unwritten past. This archaeological study, covering a remarkable duration, offers an ideal opportunity to analyze how alternative lived rhythms contribute to socio-cultural stability in the long-term. Contrary to previous approaches, this work will interpret the radiocarbon-based chronology of sites by referring to real lifespans, such as those derived from age at death and generational distance observed in collective burials, thus humanizing the history of single sites. This humanization of chronology will also consider alterations in climatic stability, as demonstrated by previous studies, and the interruption of daily life as documented by layers of abandonment in site stratigraphies. Relevant samples suitable for high-resolution radiocarbon analysis will be collected from museum collections and ongoing excavations. In addition to producing a robust radiocarbon dataset, the project will ultimately enhance the possibilities of archaeological chronology and help close the gap between short-term and long-term perspectives.

Congratulations, Rebecca and Anna!