August 27th, 2022 was my first time visiting the St. James African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church in Ithaca, New York. As a newly found Archeology major, I had decided to take a course titled “Field Methods in Community Engaged Archaeology” and was invited for an orientation to learn more about the historic church and how Cornell’s Institute of Archaeology and Material Studies (CIAMS) was working with the community to learn more about St. James’s history. I was introduced to a storied history that included the involvement of prominent figures such as Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass and a community effort to support the Underground Railroad. After this introductory session, I had the privilege of learning more about the St. James AME Zion Church and its role as a beacon for the African American community in Ithaca and the Underground Railroad by working on site. Before my experiences at St. James, I had a working knowledge of the Underground Railroad, but it's also clear that I misunderstood its nature as a community engaged form of resistance. Thankfully though, over the course of the semester, I have been able to synthesize a newfound understanding of the Underground Railroad, do real archeological work, and most importantly witness the engagement with the community that is foundational to this archeological project.

What fascinates me about archeology is trying to get closer to the lives and struggles of people who lived in the past. But what is also clear is that we cannot forget the people that are still a part of the communities that we study today. To understand why community engaged archeology at St. James is important, we must first understand the community histories of the Underground Railroad. Therefore, I would like to discuss the historical aspect of the Underground Railroad that most inspires me – community resistance. The Underground Railroad was not a physical railroad with a steady track, guiding one to freedom. But instead, was the manifestation of the bravery and courage of those fighting against injustice, whether that means fleeing slavery or rebelling against the law. And it was communities and importantly churches like St. James that were integral in this system. To explore this further, I will first discuss the historical background of the Underground Railroad, before explaining the role of community resistance, and finally discussing why the archeology of St. James is important to continuing community involvement in understanding this history.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 marked a direct assault on the freedoms of African Americans across the US[1]. The law was fully designed to persecute African Americans without care for if they had or had not escaped bondage. It denied the right to trial by jury for those accused and also inherently bribed the commissioners deciding their cases by offering $10 if the defendant was designated to be a runaway slave or $5 if they were let go[2]. This led to a situation in which the very existence of African Americans in the north was questioned. The persecution of all African Americans is perhaps best exemplified in the famous case of Horace Preston, where those representing the slaveholders argued that a “man having the accent of an Irishman was held to be an Irishman.”[3] Essentially arguing the slaveowners viewpoint that any African American should be considered a fugitive slave, on the basis of their skin color alone. It is no doubt then, that the period after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act became more dangerous for African Americans living in the US.

Despite the new laws and fears over their potential effects, communities gathered to resist or outright fight against the sending of those back south. In Upstate New York, in Elmira and Syracuse, Vigilance Committees were formed by African Americans and abolitionists in local communities soon after the new law was passed[4]. These Vigilance Committees acted to support those affected by the threat of capture, acting as collective sources of intelligence, support, and protection from those seeking to take advantage of the vile Fugitive Slave Act[5]. When people were captured and threatened with being sent to the South, community members often rallied to support those being accused, and did all in their power to prevent the law from carrying out its devastating effects.

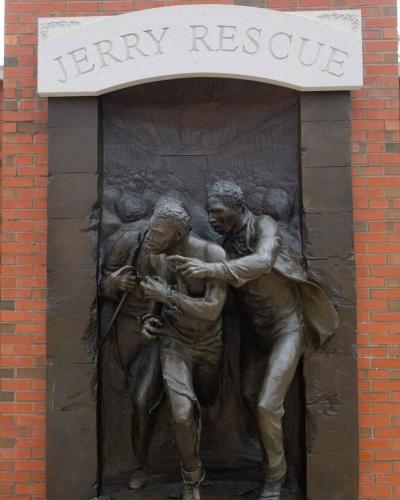

In relation to the history of upstate New York, the Jerry Rescue in Syracuse serves as perhaps the most poignant example of community resistance. On October 1851, Jerry Henry had been arrested and accused of being a fugitive in Syracuse, NY, when the local community sprung into action[6]. On that day, the anti-Slavery Liberty Party had also been in Syracuse for a convention, meaning that they were able to offer extra support when church bells were rung to signal the capture of an accused fugitive[7]. The crowd did everything in their power to hamper the proceedings. From hissing, to cause audible disruption, to literally trying to carry Jerry out of the courthouse and to a carriage to escape[8]. The crowd then resorted to throwing stones through the windows of the courthouse when Jerry was recaptured from the escape attempt and the proceedings continued[9]. While these initial attempts failed, a group of community leaders, including Reverend Jermain Loguen, the 3rd pastor of St. James, organized a plan of escape[10],[11]. About 50 people gathered around the courthouse near nightfall, and on signal, they stormed the courthouse and saved Jerry from the local authorities[12]. In the end, Jerry escaped to Canada and avoided being sent back south due to the actions of the community around him[13]. A monument now stands in Syracuse commemorating the events of this day.[14]

In my opinion, community action and cooperation is what is particularly moving about both the Underground Railroad and the history of St. James. As we can see in the Jerry Rescue, communities were able to make a difference in fighting against the implementation of the Fugitive Slave Act. However, we must also keep in mind the day to day resistance people would have engaged in. Resistance didn’t always need to be extravagant. For example, week to week “Penny Drives”, organized by women involved with vigilance committees, were a tactic used to earn money to support the efforts of those vigilance committees[15].

AME Zion churches also played an important role in the lives of African Americans by serving as community centers[16]. We know that St. James AME Zion Church was a stop on the Underground Railroad, and that the Ithaca community likewise helped many of these freedom seekers either make it to Canada or settle down in Ithaca[17]. Reverends Jermain Loguen and Thomas James of St. James were also known to have assisted those on the Underground Railroad[18]. While we cannot be 100% certain about some of the exact activities done to support those coming through Ithaca on the Underground Railroad, it is clear that St. James was an integral part of organizing a community effort to help and support them.

St. James AME Zion Church not only served as a location to shelter individuals, but also as a center for organizing different means of support for incoming freedom seekers. St. James worked to give the community a home to collectivize the efforts of Ithacans who would be willing to help those on the Underground Railroad. The role of St. James was invaluable to the work of the Underground Railroad in upstate New York. Therefore, St. James AME Zion Church represents a true manifestation of the spirit of the Underground Railroad – the resistance and collective action that helped many on their path to freedom.

The impact of St. James’s community is evident when we consider that some freedom seekers decided to settle in Ithaca instead of moving on to Canada[19]. Settling in the area surrounding the church on Cleveland Ave, they joined St. James’s community and cemented St. James AME Zion Church as a center of Ithaca’s African American community[20]. These new members of the community might then have been able to help future freedom seekers as they arrived in Ithaca. Their efforts might then have perpetuated the community efforts that once may have helped them join the Ithaca community itself.

Today as we try to uncover some of the history at St. James AME Zion Church, what I would say is similarly uplifting, is the involvement of the community in the archeology being done at the church. As an archeology student working at St. James, it’s always been clear to me that our mission is to help the community learn more about their history at St. James. I’ve been touched by the kindness that community members have shown me when I arrive on Saturday mornings to work on site. Members of the community are actively involved in the excavations and are learning about the archeological methods used on site. Furthermore, from children to adults, the community actively participates, assists, or can just observe the work being done as they walk by.

As I see it, this community involvement today is necessary to learn more about the Underground Railroad because it too was based on a community effort. We can learn from the stories of those who have been involved with the church and investigate questions that interest them. By putting the living community first, we can hopefully allow archeology to serve them in learning about their incredible historic community and church. Furthermore, by encouraging community involvement, we can freely teach archeological methods so that the younger students who join us can potentially go on to ask and answer their own archeological or historical questions.

From learning about the history of St. James AME Zion Church, the Underground Railroad, and the way that individual people have bravely stood against the vile nature of slavery, I have been truly inspired by their courage. I am very grateful to the St. James AME Zion Church for allowing me to have the opportunity to learn about their history and also to learn hands-on archeology on site. Rather than a simple archeological dig, the St. James Excavations are truly an experience to interact with and learn from such a welcoming community. Being able to talk with and spend time with community members, professors, graduate students, undergraduates, and high school students, while digging in St. James’s garden, has been an experience that will be one of the highlights I take away from my Cornell experience. St. James AME Zion Church is an important historic site in Ithaca and upstate New York, and Ithaca is truly privileged to have her be a part of its community.

[1]Eric Foner, The Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2016)

[2]R.J.M Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 53

[3]Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, 383

[4]Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, 363

[5]Foner, The Gateway to Freedom

[6]Foner, The Gateway to Freedom, 143

[7]Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, 366

[8]Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, 367

[9]Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, 363

[10]Foner, The Gateway to Freedom, 146

[11]“History of St. James,” St. James AME Zion Ithaca, accessed October 24th, 2022, https://st-jamesamezionithaca.org/partners

[12]Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, 383

[13]Foner, The Gateway to Freedom

[14]“Jerry Rescue Monument,” Freethought Trail, accessed October 24th, 2022, https://freethought-trail.org/trail-map/location:jerry-rescue-monument/

[15]Foner, The Gateway to Freedom, 82

[16]Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance. (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013)

[17]“History of St. James,” St. James AME Zion Ithaca, accessed October 24th, 2022, https://st-jamesamezionithaca.org/partners

[18]“History of St. James,” St. James AME Zion Ithaca, accessed October 24th, 2022, https://st-jamesamezionithaca.org/partners

[19]“History of St. James,” St. James AME Zion Ithaca, accessed October 24th, 2022, https://st-jamesamezionithaca.org/partners

[20] “History of St. James,” St. James AME Zion Ithaca, accessed October 24th, 2022, https://st-jamesamezionithaca.org/partners