What do your clothes say about you? When you wake up in the morning and get dressed, do you meticulously plan out your outfit, or do you just grab whatever’s clean and comfortable and throw it on? Either way, we all have a deeply personal relationship with the clothes we wear. This is why I wanted to delve into the recovered textile material from the St. James site.

Generally speaking, textiles themselves don’t preserve well in the ground. Up until the last 70-80 years, all fabrics were made from natural fibers like wool, cotton, linen, etc., all things that break down over time, especially when exposed to moisture. I was incredibly excited to learn that there have been several intact pieces of fabric found at the site, some of which are relatively large. There’s a pretty wide range in the collection, from small, swatch-like pieces of woven fabrics, to large intact pieces such as a gold-toed sock. However, one piece really caught my attention. What was originally described to me as a large, unidentified piece of tan fabric turned out to be an almost completely intact garment of some sort. The item was excavated in 2022, and from my understanding has sat in its bag in storage since then, unidentified.

Textiles play a tricky role in the archaeological record. Understanding the ways in which individuals dressed and decorated themselves is incredibly important in not only understanding cultural ideals but also individual identities. However, generally speaking, it’s quite uncommon to find complete garments in the field, especially when looking at older time periods. This leads to a lot of knowledge surrounding fashion and dress of various time periods coming from outside representations, such as artwork and texts. We also are able to gain insight via the tools left behind in textile production. Needles, loom weights, and spindle whorls can be found in places where textiles aren’t preserved in the earth, giving us some insight into the inner workings of textile production.

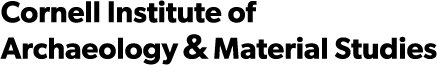

Figure 1. Overhead look at the garment, which has been folded and posed in a way that I believe shows the original construction and seamline of the pieces, alongside a small piece of lace and a piece of elastic that was found entangled in the piece (photo by author).

Textile archaeology also requires quite a bit of general craft knowledge. I spent my undergraduate days working as a seamstress in a bridal shop, and I have been able to fully understand the ins and outs of clothing production and tailoring, which I think is a major advantage in this field. This highlights the benefits of involving all types of craftspeople in the field. Because of my non-academic work experience, I can look at a garment and understand how it was made, the shapes in which the fabric was cut, and why, I can tell if it’s been altered, what it’s made of if it is well made or cheaply made, and so much more. I think that translates to other material studies in archaeology too. Someone who makes ceramics will have a much more embodied knowledge of ceramic production in the field, and so on. All of the individuals that I’ve met who identify as textile archaeologists have all had some kind of interest in fiber arts outside of archaeology, whether that be sewing, knitting, weaving, etc.

Excavating fabric and soft textile material can be very different than rigid artifacts that can be sifted. Buttons and other hardware from clothing can be sifted for and handled with less worry around damage. Buttons can be made from a wide variety of materials, from bone, wood, metal, or plastic all being popular, many of which have been found at this site. As stated earlier, moisture is a major issue when it comes to excavating textiles, and this is why many sites rarely find preserved fabric in the ground. Moisture in the earth can cause the fabric to degrade over time, sometimes completely degrading the fabric to nothing. While we have found several pieces of fabric at the St James site, many of them are relatively fragile, having been heavily affected by the moisture in the soil.

Once the artifacts were removed from the field, they would have been taken to the lab to be cleaned and organized for future reference. The issue with textiles is that they can be very easily damaged in the cleaning process, and since the St James project does not have a textile specialist on hand, a majority of the textiles that came out of the field faced minimal cleaning, aside from potentially some light brushing to remove dirt.

Object 3, or the garment I will be looking closely at in this piece was excavated in 2022, from unit 6 of the site. Initially, when I was first handed this piece, it looked just like a large piece of tan fabric wadded up in a bag full of dirt and stones. In fact, there were many rocks and dirt clumps that were fully attached and entangled in the garment. I learned that this piece was most likely never cleaned at all when it was removed from the field, as there was fear of damaging something so delicate. There are several ways to clean archaeological textiles. Using water and mild detergent can be used in some cases, but again, any of these cleaning methods would require prior testing to prevent damage. Ultrasonic cleaning is also used, where the fabric is put in a solvent, which is then agitated by sound waves which create small bubbles that agitate any dirt on the piece to clean it. I have also seen discussions around laser pulsation being used to clean archaeological textiles, although this seems to be a new topic. I ended up using a variety of small brushes to dust out the pieces and slowly pick out any intertwined stones, artifacts, and other pieces of textiles. This was the only method I felt comfortable using since I had no real knowledge of the piece prior to this.

When I first got my hand on object 3 the first thing I noticed was the fabric. Nearly every other fabric piece that has been found at the site has been a woven, natural fiber material, or a material similar to leather or fur. Object 3 is a knit fabric, which refers to the fact that the fibers of the fabric are knit together to make the fabric stretchy, as opposed to woven fabrics which generally have a lot less stretch to them. Not only is this a knit fabric, but the fibers themselves have stretch to them as well. There is a significant amount of fraying in the fabric, and fromgently pulling the frayed fibers I could see that they had stretch to them. As I was brushing off dirt clumps and picking through the frayed fibers, I also found what looked like a long piece of elastic, about 40 inches in length, potentially a part of a waistband. The combination of the elastic fibers and elastic waistband indicates that Object 3 is a pretty recent piece, at least post-WW2.

Figure 2. Elastic waistband remnants (photo by author).

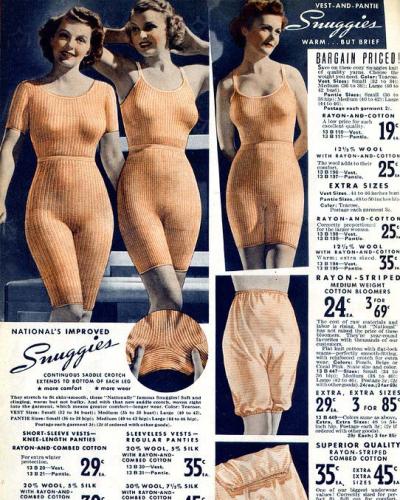

Entangled with Object 3 was a small piece of lace, similar to what would be found on women’s lingerie or underwear. This also appeared to be synthetic fiber, and machine-made lace versus hand-made bobbin or tatted lace. It doesn’t seem like the piece of lace was originally attached to the item, but considering how intertwined it was it’s fair to say they were probably deposited at the same time as each other.

Figure 3: Lace piece found entangled in Object 3 (photo by author).

So what exactly is the garment? It’s hard to say exactly, but based on the fabric, cut, and construction, it seems like some type of undergarment. The garment is vaguely pant-shaped, with a gusset at the crotch made of a slightly different stretch fabric. Initial guesses lead me to believe it’s some kind of men’s underwear, as a men’s gold toe sock was also found at the site. Upon further research, I think it may be some kind of thermal underlayer. Even though synthetic fabrics became more widely used post-WW2, cotton was still the predominant fiber used in men's and women’s underwear. Women’s pantyhose and other body-shaping garments such as girdles or bras had been using synthetic fabrics such as nylon since the 1930s.

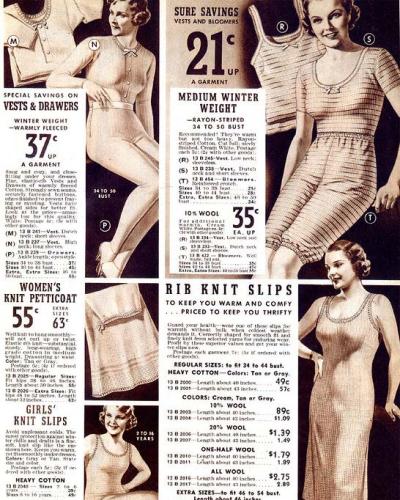

Further inspection of the garment makes me lean more towards this being a piece of women’s shapewear or thermal underwear for one specific reason; the gusset. The gusset is a small piece of fabric that sits at the crotch of the garment and seems to be made of a different blend of fibers, most likely nylon mixed with cotton. Men’s underwear and underlayers usually have a fly in the front of the garment, even in long johns or thermal underwear. This garment does not have that, it has a lower gusset that does not have this flap opening, which was more standard in women's underlayers and pantyhose. The garment is also very small, with what appears to be the leg holes only measuring about 5-6 inches wide, or about 12 inches in circumference without stretch. Because of the age of the garment and the amount of dirt embedded into the fabric, it’s hard to say how far this fabric would have been able to stretch when new, so it may have been able to stretch to adult size, or left to be worn by a child. As of now, my current guess sits at a women's or girls' pair of shapewear or thermal underwear. I have yet to find any image references of something that truly matches the cut, design, and fabric of Object 3, but I’ve included some advertisements from the late 1930s that could be of similar garments.

Figure 4. Catalogue page via National Bella Hess Fall and Winter Catalogue 1937-38.

Figure 5. Catalogue page via National Bella Hess Fall and Winter Catalogue 1937-38.

Textiles, fashion, and dress are simultaneously representations of cultural ideas and movements while also being an everyday form of expression. What does something like Object 3 tell us about the individuals at the St James church? While this garment opens the door for dozens of questions, I think textiles in archaeology allow for a more intimate look into the everyday lives and identities of individuals. While there is still much more analysis to be done on the exact specifications of this garment and what it is, who may have owned it etc., what we do know gives us a small peak into the everyday life of an individual, who woke up, and got dressed just like we all do today.

References:

[i] National Bella Hess Fall and Winter Catalogue, 1937-38.

St. James Excavation Records, Excavation forms on file, Cornell University, Ithaca New York.